|

| Yesterday's Main

Street, Kathy, January 2, 2025, Creative Commons, Flickr.com. |

|

| Yesterday's Main

Street, Dainaar, April 2, 2010, Creative Commons, Flickr.com. |

When I began investigating my family background and found that

the Irish Carney/Kearney family line lived in Chicago from 1860 on, I was even

more passionate about learning about life in early Chicago. Following the

Irish, my German, Greek and Czech ancestors came to make their home in this

young city. I wanted to walk the streets my people walked, see the sights they

saw every day, hear the sounds that might have soothed or tormented them, and

even smell the scents that surrounded them.

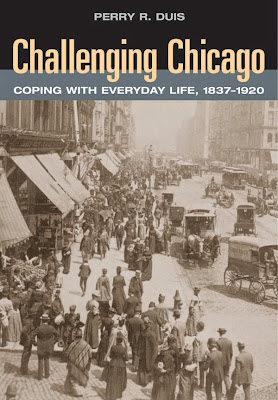

Fortunately for me, I came across the book Challenging Chicago: Coping With Everyday Life, 1837-1920 by Perry Duis.

The author goes way beyond the surface of sights and sounds. He plunges the reader into the gritty but also glorious world that was Chicago in this time period. From this book, I learned the risks and the obstacles that challenged my people, but I also learned about the opportunities.

|

| Used by permission of publisher, University of Illinois Press |

The author goes way beyond the surface of sights and sounds. He plunges the reader into the gritty but also glorious world that was Chicago in this time period. From this book, I learned the risks and the obstacles that challenged my people, but I also learned about the opportunities.

Dr. Duis is a master at painting a picture with words of

what it was like to live in Chicago in those early years. Although this is a scholarly

work covering the history, social mores, technological advances, and much more

of this period and place, it is as readable and engrossing as a historical

novel. However be advised, I may be prejudiced as I love nineteenth century

Chicago!

In the introduction, Duis tells his readers the purpose of

this book: to explain the challenges of living in a new, fast growing city and

how its denizens dealt with them:

“The millions of all social classes who flocked to American

cities…needed to resort to survival strategies. Urban life was a new experience

for most of them. Raised on farms and in small towns, both here and abroad,

they were often unprepared for what lay ahead. Many found that cities were far

more congested, crowded, dangerous, unpleasant, immoral, and unhealthy than

they had anticipated.” p. xii Duis

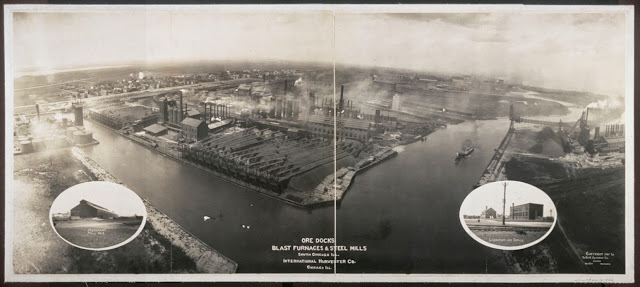

First, Dr. Duis tells us what forces helped create Chicago

and other cities. By the mid 1800s, the industrial revolution was taking hold in the United States. Farm

workers living in poverty in rural America and in Europe began seeking

employment in the new factories that were springing up in cities like New York

and Chicago and were hungry for workers. To give an idea of the astonishing

rate of population growth in Chicago, Duis writes:

“A populace of 4,170 in 1837 became 29,963 in 1850 and

109,260 in 1860, and it was on its way to three times that figure by the time

of the Great Fire in 1871.” p. 7 Duis

Here is a photograph of State Street c1893 which shows the congested conditions of Chicago living:

With such rapid growth, there wasn’t much time to pay

attention to the environment – the land the people lived on and traversed. People,

including the city fathers, were focused on business. But nature was not to be

ignored.

Here is a photograph of State Street c1893 which shows the congested conditions of Chicago living:

|

Traffic on

State Street, Chicago, U.S.A., Washington, D.C. :

J.F. Jarvis, publisher, c1893,

LC-USZ62-101801,

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Division

Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

|

From the time before the first Europeans came to the site of

Chicago in the late 1600s, the area was plagued by mud much of the year. In

their book Chicago: Growth of a

Metropolis, Harold M. Mayer and Richard C. Wade explain the cause of that

mud:

(It) “…was the result

of ancient geologic forces. More than four hundred million years before, the

site lay beneath a tropical sea ….Before the waters receded there was deposited

on the sea bottom the material (limestone) that constitutes the bedrock of

Chicago….Above the limestone, glaciers left layers of impermeable clay that

prevented the draining off of surface waters and created a high water table.”

p. 3 Duis

|

# 69 State Street, South from Lake,

Views of

Chicago, Carbutt, Photographer,

Chicago History Museum, used by license.

|

In 1837, the city declared that “No dung, dead animal or

putrid meats and fish or decayed vegetables (were) to be deposited in any

street, avenue, lane or public square.” p. 5 Duis

Just walking in the city was a nightmare:

“The lack of sidewalks forced pedestrians to walk on the

sides of the road, where debris, garbage, stray animals, mud, standing water,

and dust impeded daily travel.” p. 5 Duis

|

| Ore docks, blast

furnaces & steel mills, South Chicago, Ill., International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill., Geo. R. Lawrence Co. , copyright claimant, c1907, C-USZ62-41402, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. |

A basic facet of life is shelter, and I have long wondered

the kind of housing my Chicago ancestors had. Different pieces of evidence

(including the sad finding that an infant of the Carney/Kearney family was

buried in the pauper’s area of Calvary Cemetery, the fact that my people likely

left Ireland in the famine years, and the family story that my great

grandmother was in an orphanage) attest to the probability that the

Carney/Kearney and Duffy families were poor. Perhaps part of the reason I have

trouble locating them in the city directories and federal census records is

because of their poverty. Duis tells us that many Chicago families moved every

May 1st, but poor families moved even more often, sometimes to avoid

back rent they couldn’t afford to pay or in the hope of securing cleaner, less

crowded lodgings:

“For the very poor, eviction or the search for more sanitary

and safe tenements often led to the transfer of their meager possessions every

few months. Their stay in one place was often so brief that they used

neighborhood saloons as permanent mailing addresses.” p. 85 Duis

Too bad the saloons didn’t keep

ledgers filled with addresses of the neighborhood denizens!

Another challenge for Chicago’s

workers was finding food. Due to crowds, increasing commuting distance from

work, and unreliable public transportation, working people couldn’t get home

for lunch. Saloon owners saw a way to

capitalize on their roles as post box and job message board. Why not serve lunch

to bring in customers to eat and, of course, drink? Initially, saloons charged

for these noon meals, but when a politician/saloon owner started handing out

free oysters (p. 157- 158 Duis), the concept if free food to lure customers

spread across the city. Thus, was born, as Dr. Duis tells us, a new concept –

the free lunch.

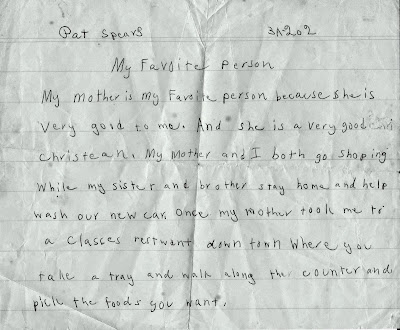

But that wasn’t the only thing

Chicago gave America in the area of eating. When I was a little girl, my mother

took me downtown to a cafeteria. I was mesmerized by all the food choices! This experience inspired the essay below from me in the third grade:

But I

had no idea then that my city invented this restaurant phenomenon. In order to

reduce the cost of lunch for working women, the Ogontz Club came up with the idea to do away with wait staff and instead, let patrons

choose their food from large tables and carry their plates back to the seating

area. p. 159

|

Image from

page 208 of “Blasts” from “The Ram's Horn” (1902),

Chicago, The Ram's Horn Co., Internet Archive

Book Images,

Flickr.com.

|

|

| Written by Pat Spears, 1953 school assignment, John M. Palmer Elementary School, Chicago, IL |

Thus was born our modern day cafeteria. A fellow blogger, Ms. Jan Whitaker, wrote a wonderful poem, “The Cafeteria,” which perfectly captures my fascination with this form of dining.

To conclude, we have taken just a

quick visit to the wonderful world of nineteenth century Chicago, courtesy of

Perry Duis. But there is more to explore in his historical tour guide,

including how early Chicagoans sought to escape the problems of life and spend

some moments enjoying what the city had to offer, covered in Part Four: Spare

Moments.

categories: genealogy tools