Genealogists are familiar with many types of records,

including vital (birth, marriage, death), church, court, and land documents.

But the medical testimonial is a new one for me. Here is an example:

|

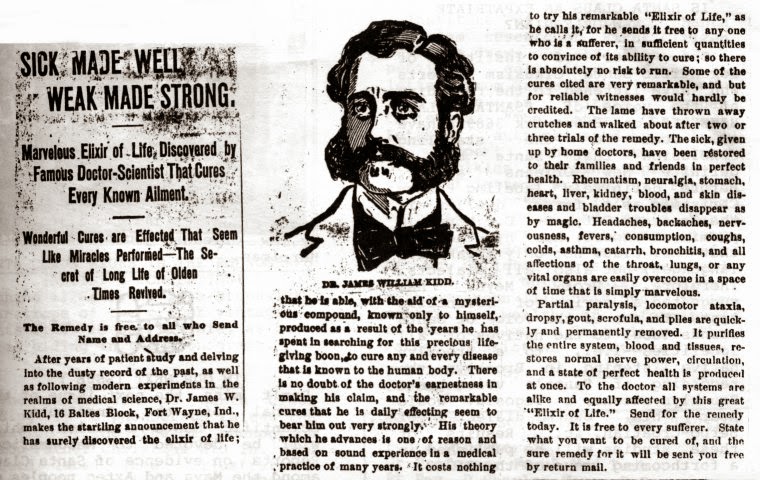

| Patent Medicine

"Elixir of Life" ad, c. 1901, Infrogmation 15:49, 9 May 2008, Wikimedia. |

The Wikipedia definition of a “medical testimonial” is:

“…a testimonial or show consists

of a person's written or spoken statement extolling the virtue of a product. The term "testimonial" most

commonly applies to the sales-pitches attributed to ordinary

citizens….” 1

TheFreedictionary.com adds to the above definition that these

testimonials

“…consist… of individual

personal accounts of healing without statistics or controlled scientific

experiments.” 2

All records have a purpose. Let’s see what the impetus was

for medical testimonials that became wildly popular in late eighteenth and

nineteenth century America when the advantages of modern medicine were lacking.

|

Broussais

instructs a nurse

to carry on bleeding a

blood-besmeared patient.

Wellcome

Library no. 16372i, Wkimedia.

|

So many ailments and diseases that in the past could make your life very

uncomfortable or might even kill you, nowadays are controlled by early

detection and/or effective medical interventions. But our ancestors, who lived

in America up until the early twentieth century, did not have access to the

medical knowledge and treatment available today.

Medical knowledge and care was not very developed in America

in the 1800s. The average person had a healthy suspicion of the chances for

getting better under a doctor’s care because so many did not. People often

treated themselves with the herbs and later patent medicines that became necessities for nearly every home partly due to the rise and spread

of advertising and medical testimonials in newspapers from the mid-19th

century.

|

Kilmer's

Swamp Root (a patent medicine),

Edmonds Historical Museum,

|

What was

medical education like in America in the 1800s? I consulted the online article,

Gale Encyclopedia of US History: Medical Education. From this site, I learned that medical

schools were sparse in 19th century America. They were simply

businesses, and those who ran them were in it for the student fees. Courses

were short, and there were no labs or opportunities to work with patients.

Why was it important for patent medicine hawkers to have ads

and testimonials? Patent medicines, like any product, need recognition by the

public for sales to occur.

Although several brands of patent medicines had been

available in England and America since the 1600s, it wasn’t until the middle of the nineteenth century that this industry could

say its products were found in almost every American home. And this happened

for three reasons (rise in literacy rates, spread of newspapers and with them

newspaper advertising) which Peggy M. Baker, Director & Librarian, Pilgrim Society & Pilgrim Hall Museum, explains in her article, “PATENT MEDICINE: Cures & Quacks”:

|

Dr. Miles'

Anti-Pain Pills, Edmonds

Historical Museum,

Edmonds, Washington,

Joe Mabel, 30 April 2009, Wikimedia. |

“The expansion of public elementary

schools meant that everyone could read newspaper ads that promised (unproved)

cures and provided (unreliable) testimonials. The craving for news from the

front during the Civil War meant that more Americans read more newspapers,

giving patent medicine manufacturers access to more customers.

The discovery of cheap wood pulp paper and improvements in the printing process meant that advertising volume could grow by leaps and bounds. Newspapers became filled with ads promising quick, easy, inexpensive and sure cures for diseases both dreadful and mundane.”

.jpg) |

Oregon Paper

Mill, “…piles of pulp… made from wood and

which…will be made into great rolls

of paper.”

OSU Special Collections & Archives, 10 July 2009, Wikimedia.

The discovery of cheap wood pulp paper and improvements in the printing process meant that advertising volume could grow by leaps and bounds. Newspapers became filled with ads promising quick, easy, inexpensive and sure cures for diseases both dreadful and mundane.”

But what does all this have to do with genealogy? Medical

testimonials are actually a unique genealogical record group, one that I never

came across before finding one through GenealogyBank.com by one of my ancestors.

Many of you are familiar with GenealogyBank and already have used its huge

newspaper database. For those who haven’t yet mined this vast resource, this is

how a Wikipedia entry describes the company:

|

| Logo used by permission of GenealogyBank |

“GenealogyBank.com is a commercial genealogy website housing a database that contains over one billion digitized records from U.S. newspapers and historical documents for researching family history online.” 3

I was doing a search on my cohort families in GenealogyBank. In my years of searching

databases, I have learned a few techniques to make the search more focused,

such as using quotation marks around the target name or phrase.

When you log in

to GenealogyBank, you see a simple search screen. But I wanted to limit my

search to Illinois newspapers, so I scrolled down to “Historical Newspapers”

and clicked on “Newspaper Archives.” The screen that appeared had a list of

states in which to search and I checked “Illinois.” But you can “drill down”

even further. When you double click on “Illinois,” you will see a listing of

cities/towns. I clicked on “Chicago.” (note: Many times you will not want to

limit a search, especially at the beginning. Putting too many limits may result

in your missing an important article.)

Next, I filled in the search box fields:

Ancestor's

Last Name: “Cosgrove”

First

Name: “Matthew”

Include

Keywords: “Chicago”

Exclude

Keywords

Date

Range: 1850-1880

Date

Date

I clicked on “Begin Search” and the initial results screen

appeared:

Date: Sunday,

June 24, 1888

Location: Chicago,

Illinois

Paper: Daily

Inter Ocean

Article type:

Ad/Classified

When I clicked on “Ad/Classified,” the second results

screen appeared. At the top of the page, GenealogyBank gives you source

information, including the type of newspaper article, the date, the name of the

newspaper, the volume, issue, section and page. For my Cosgrove search this is

what came up:

Advertisement

Date: Sunday, June 24, 1888 Paper: Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago,

IL) Volume: XVII Issue: 96 Section: Part 3

Page: 20

Below this citation is the actual article. And what a

surprise it was!! GenealogyBank highlights your search terms in yellow, so I

scrolled down the page, looking for “Matthew Cosgrove.” This jumped out at me:

“Miss Katie Frances Cosgrove is the 13-year-old daughter

of Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Cosgrove, whose residence is at No. 303 South

Desplaines street, this city.”

What a treasure trove in the first sentence – names and addresses! And the details fit my

research into the Cosgrove family in Chicago city directories and federal

census documents.

As I scrolled down, I came to a line drawing of Katie –

perhaps the only existing depiction of her.

In the text, we read that according to her mother, Mrs.

Cosgrove, “Ever since Katie was 6 or 7 years old she has been troubled with

catarrh…and though we tried many things, nothing seemed to do her any good.”

Next is the point of the testimonial, for this is where

the reason for this whole story in

the advertisement comes out:

Again in the words of Mrs. Cosgrove, “We heard of some of the remarkable cures of chronic catarrh by Dr. J.G. Carroll, now at No. 96 State Street. Several months ago I took Katie to the doctor’s office for the first time….She took the doctor’s treatment at once and one month afterward she was very much better. She has continued to improve right along ever since, and now feels and looks better than she had for years.”

And the testimony does not stop with Mrs. Cosgrove. Katie

herself is also called upon to praise Dr. Carroll:

“The doctor’s treatment cleared my head at once, and made

it feel as if nothing had ever stopped it up.”

After discovering this document on GenealogyBank, I wondered

how the Cosgrove family came to be featured in a newspaper. They were an

ordinary family with no renown or fame. That’s when I began researching medical

testimonials and found how prevalent this type of advertising was at this time.

But how were these “testifiers” located? How were they persuaded to testify?

As early as 1849, the American Medical Association (AMA) was

warning the public of the dangers of “quack remedies and nostrums.” In 1911, the AMA published several articles investigating the

fraudulent use of medical testimonials under the title Nostrums and quackery. It appears that enterprising entrepreneurs

realized the value of the personal touch in building trust of would be

customers of patent medicines or doctors who provided quick cures. Often

inventors of the products would pursue advertising themselves but as the field

grew, they would seek partners.

According to one of the articles in the set mentioned above, a whole new job was created by the industry

called “medical testimonial gatherers,” and men were solicited through

newspapers to fill the jobs as reported in the American Medical Association

articles mentioned above. These gatherers would offer small remuneration or

even photos to perspective testifiers.

.jpg) |

Still from

the American silent film Traveling Salesman (1921),

from page 60 of the July 1921 Photoplay magazine, Wikimedia.

|

The American public remained avid users of patent medicines

and quack cures pedaled by “doctors” through advertising and were unaware of

the actual ingredients that were in these products into the early twentieth

century. As explained in a Wikipedia web page on patent medicines, it wasn’t

until the First Food and Drug Act of 1906 that the industry faced its first

regulation:

“This statute did not ban the alcohol, narcotics, and

stimulants in the medicines; it required them to be labeled as such, and curbed

some of the more misleading, overstated, or fraudulent claims

that appeared on the labels.”4

|

| Harvey Washington

Wiley, "Father of the Pure Food and Drugs Act, ” Ca. 1900, DCPL Commons, Wikimedia. |

But it would be another 32 years, until 1938, when the

statute would be amended to ban patent medicines.

Footnotes

- Testimonial, from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, online < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Testimonial>, downloaded March 2014.

- Detoxification, TheFreeDictionary, online <http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Detoxification>, downloaded March 2014.

- Genealogybank.com, from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, online < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GenealogyBank.com >, downloaded March 2014.

- Patent medicine, from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, online <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_medicine>, downloaded March 2014.